Can you explain the Chinese “sharing economy” phenomenon?

Real sharing economy companies like ride-hailing platform Didi Chuxing and Airbnb-like vacation rental platforms Xiaozhu and Tujia have been around for some time in China. Like their American counterparts, the sharing economy players that exist nowadays are, by and large, firmly established and either dominate the markets they are in or are locked in duopolistic competition with domestic or international rivals.

First, let me say that there’s two kinds of “sharing economy” in China: There’s the normal kind of sharing economy typified by pioneers like Uber and Airbnb who distribute shared goods and services but do not actually own them.

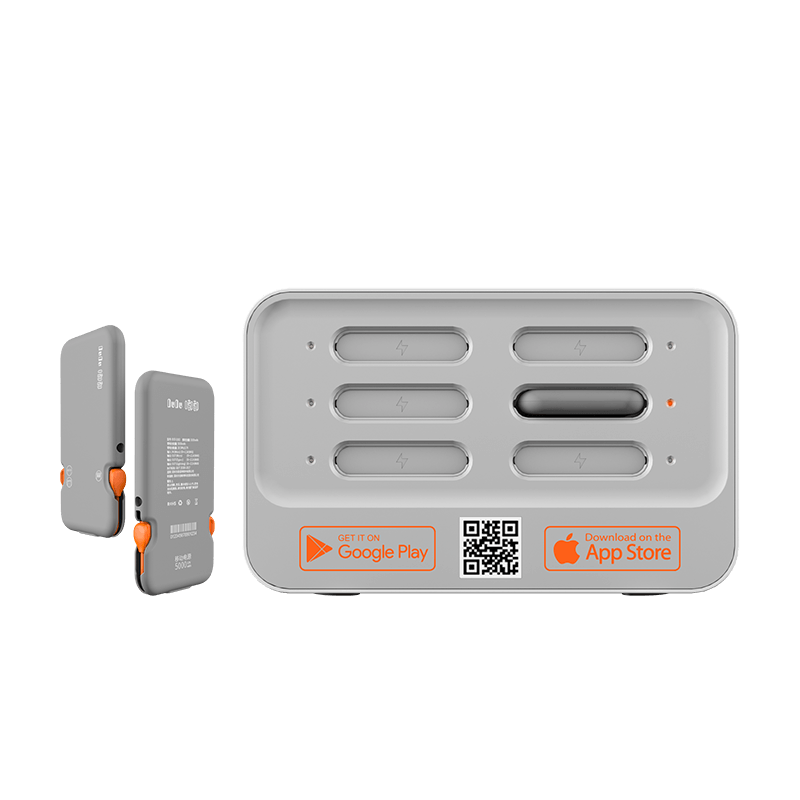

The latter is the kind that you hear about often in tech media: bike sharing, power bank rentals, basketballs, and sex dolls (yes, really). The list goes on and on, and a lot of money (to the tune of $247 million in Series A funding between April and May 2017)[1] has been spilled to capture value in this thriving new space.

And now, back to the pseudo-sharing economy, which is really where the action is at. While the normal sharing economy model in China is generally similar to that in the West (give or take some aspects like China’s high-competition dynamics), the pseudo model is uniquely Chinese in several ways. A good way to understand these distinctions is to compare this with the sharing economy outside of China.

A. Competition 1

Competition is high for normal sharing economy players like Didi Chuxing and Tujia, but for the new class sharing economy startups. extremely high. Let’s take dockless bike sharing — a “last mile” solution where users can scan a QR code on bikes to unlock them.

And leave it anywhere in the city (it’s also one of China’s “four great new inventions” along with the high-speed rail and Alipay.)

In a recent count, there are 40 bike sharing companies operating in China, with ofo and Mobike as the leading players.

If you can imagine forty startups, many with venture funding in the tens of millions U.S. dollars. Battling to control key Chinese cities like Beijing or Shanghai in less than two years. Then that’s the kind of competition that exists for bike sharing and other similar sharing schemes. China’s formerly third-largest bike sharing startup that raised $90 million, shutting down.

Competition 2

One morning recently in Shanghai, I caught a glimpse of some suspicious behavior. I was walking down a tranquil, tree-lined street when a muscular man lumbered past carrying two orange-and-silver Mobikes. As he swept by, a wheel touched the ground and set off an alarm, causing him to heave the bikes even higher in the air. The man was not a bike enthusiast, but he wasn’t a thief, either. As I watched him slip down a side alley and emerge moments later empty-handed. I realized that he was a foot soldier in the bike-sharing wars, dumping competitors’ bikes in hard-to-find places. Rounding the corner, I saw the result of his handiwork: a sea of bikes in almost every hue. Yet not a single orange-and-silver Mobike was in sight.[4]

Given the winner-take-all nature of the sharing economy. Competition is definitely high for American startups in this space, doubly so in the case of Uber vs. Lyft. But outside key shared assets like cars and homes. Many of the sharing economy failures were due to lack of product-market fit rather than direct competition.[5]

Bike-sharing gone bad

B. Backed by Tech Giants and the Government

Another unique characteristic of China’s pseudo-sharing economy is that it’s backed by two very powerful forces: Tech giants like Alibaba and Tencent and the government. China’s largest Internet companies will begin pouring money it. For example, ofo’s $700 million funding round led by Alibaba and Mobike’s $600 million round led by Tencent. Then there’s the government, which set a new policy framework to spur the growth of the sharing economy. Deemed important to the national economy.

For the American counterparts, venture capital funding rather than strategic investments from large tech companies has been the pattern (outside of Google Venture’s investment in Uber. Which is part of a long, complicated relationship than a strategic one.) And more than once government and municipal regulators have thrown a wrench in the plans of sharing economy companies.[8]While the Chinese sharing economy is blessed with the tailwinds of large big tech and government backing, those in the American sharing economy are often flying solo with themselves and their investors.

You probably won’t see this happening in China

C. Lack of Trust

Traditionally, the sharing economy works only if there’s trust, often enabled or enhanced through technology. Why would I take a ride in your car or sleep in your house if there’s even 0.1% of getting murdered, just like in the movies? American startups have circumvented this issue of stranger danger through technology. Such as a review system or careful background checks for sharing economy participants. Using Ben Thompson’s Aggregation Theory. These companies have commodified trust, while psuedo-sharing economy startups in China haven’t for the most part.

That’s why you see stories like a bike sharing company going bust after losing 90% of its bicycles or an umbrella-sharing company losing almost all of its 300,00 umbrellas. Or Bluegogo’s controversial shutdown without paying back the $15-$45 deposits back to its users. Both sides, the companies and the users. Suffer from a lack of trust, which would mean death for these companies without technological interventions. Mobike bicycles feature GPS location to prevent theft. The fact that you have to use a QR code to use “shared” goods and services allows companies to track user data and penalize bad users. Even to the extent of negatively affecting users’ social credit score and limiting their chances to apply for a loan,

In fact, I see China’s QR code revolution as largely responsible for allowing the pseudo sharing-economy startups to exist in the first place. Much like how the smartphone made ride-sharing possible from getting picked up thanks to accurate GPS location to trusting that the driver will get to your destination with the help of Google Maps

D:Achieve sharing economy

QR codes enabled Chinese users to get exactly what they want with low risk of being tricked. Whether it be a bike or an umbrella, simply by scanning a QR code. That you can put a QR code on literally anything means that many things will. And already have, become sharable goods. So while a lack of trust is a barrier in China’s pseudo-sharing economy. That doesn’t mean that certain Chinese innovations can’t address those concerns — and even create better conditions for sharing.

Last but not least, Chinese people like to share

In a survey, 94% of Chinese internet users said they would like to share with others over the Internet. Which is the highest rate among all countries. From cultural aspects such as sharing food with everyone at the dinner table to communal sharing during Mao’s China, sharing is at the heart of China’s social fabric. This deep-seated social practice combined with technology has created the sharing economy phenomenon in all its forms in China today. It’s not only an extremely large sector of China’s economy with $500 billion in transactions among 600 million Chinese. But it’s also a tremendously exciting trend that is probably already shaping the future of Chinese lifestyle.